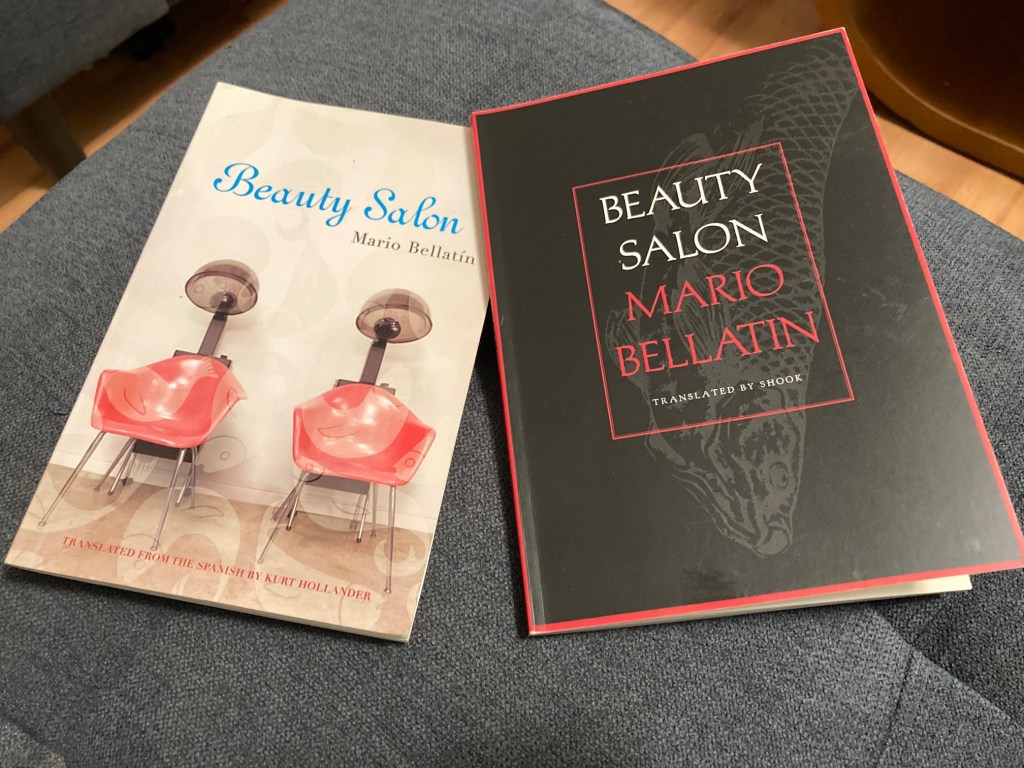

I read Beauty Salon, translated by Kurt Hollander, for the first time in 2015, on the recommendation of a friend, and was riveted by it. I don’t re-read things often, but I decidedly wanted to revisit this, and so I was very excited to hear that Deep Vellum was releasing a new translation, done by Shook.

New translations of contemporary literature are like remakes of recent movies. Already? you might think. What was wrong with the first one? Especially if you consider how much good literature never gets translated, you can find yourself thinking in terms of an economy of scarcity and being irritated at this poor use of translation resources. But at a moment when there is increasing impetus to recognize the work that translators of literature do, we might also resist such scarcity thinking (and haven’t we learned by now to resist the terms imposed by austerity??) and instead see a new translation as being something like the cover of a great song. Who would want to live in a world in which there is only one version of Hallelujah (even if that would save us from all the bad versions…)?

Much like a good cover song, a new translation can also be an opportunity to revisit the original and appreciate it differently. An invitation to re-read a particular text in a new moment, a new context. Even if that moment is only a few years later — it has, after all, been an eventful few years.

Indeed, part of my interest in re-reading Beauty Salon was a curiosity about reading it during a pandemic — the novella is about a man who is caring for people dying in a pandemic of some kind. Though it seemed quite obvious to me that it was an allegory about AIDS, I was curious to see if it would come across differently, now.

But it didn’t. I am often in favor of untethering texts from their historical frameworks and inviting connections to other moments, but this text is so clearly about queer men, and the particular kinds of stigmatization that the AIDS epidemic involved, that it would feel like a violation, to me, not to read it that way.

But it was a real pleasure to re-read the book, which was even more marvelous, unsettling, and beautiful than I remembered. A kind of monologue by a man who has converted his beauty salon into a place for men to die, and has also acquired a hobby of keeping fish in various tanks, it’s fascinating for the very specific note it strikes: cold, but not unfeeling; unsentimental but not detached. There’s a matter-of-factness that is not exactly pragmatism, but rather, something like directness. This is how the disease kills you. These are the problems you face, running a hospice. This is how I disposed of a tank of fish I decided to get rid of. The tone is really particular and really unique, and it is absolutely crucial to the text.

Which brings me back to the new translation. Here I must confess that I made what I now recognize was a big mistake, which is that I started reading the new translation with the old one right next to me, going back and forth between them to compare. This was unfair to the new version — I should have just sat down and read it, on its own, to give it a chance to be itself. I think I would have appreciated it more that way. But as it is, the prose is quite, quite different, and I have a very strong preference for the older text. Maybe this is because it’s the one I read first, though I don’t think that’s why. But let me give you a few examples, so you can decide for yourself.

I think it was at the same shop where I learned that in certain cultures the mere contemplation of the carp was a serious pastime. I began to devote hour after hour to swooning over the reflections emitted by their scales and tales. Someone later confirmed for me that such an activity was a strange form of amusement.

But what no longer seems at all amusing is the ever greater number of people who come to the beauty salon to die.

*

I believe it was in the fish store where I heard that the very act of contemplating carp was considered a pleasure in certain cultures, and that’s exactly what happened to me. I spent hours and hours admiring the light reflected by their scales and tales. Someone later remarked on this strange form of entertainment.

The increasing number of people who come to die in the beauty salon is no form of entertainment at all.

Or:

But returning to the fish, at some point I also grew tired of keeping solely guppies and golden carp. I think it has to do with a deformity of my personality: I quickly tire of the things I’m attracted to. The worst part is that I then don’t know what to do with them.

*

But back to the fish. At one point I grew bored of having only guppies and golden carp. I think it’s a personality flaw. I grow tired of things very quickly. The worst of it is that afterwards I don’t know what to do with them.

And one final one:

Even so, I felt there was still something missing to make the salon truly unique. That was when I thought of the fish. They would be the touch that gave the salon its special nuance.

*

I still felt, though, that something was lacking in order to make this beauty salon a truly unique place. That’s when I thought of the fish, just the thing to make the place special.

Maybe it’s just me, but I think there is a huge difference between the two prose styles — one is lyrical and smooth, and the other is clunky and awkward (I won’t tell you which one is which — either it’s obvious or it’s not!). In the end, I just could not bring myself to read the new version, when the old one was sitting RIGHT THERE and was just so much more pleasurable. Another thing about the new version that irked me was, first, that rather than being one continuous text, there are page breaks sprinkled throughout, creating something like little chapters. Which is distracting, and messes with the artful flow of the text. And second, the new one has missing sentences, and in some places, the meaning is actually different! It is possible, of course, that the new version is actually more accurate or faithful to the original (though the translator’s note at the end says “Reader, I have taken liberties.”), but regardless — I like it less. And though I don’t feel entirely justified making this claim, given that I didn’t actually read the entire new version on its own, I’m tempted to say that the old version is more queer. Consider the contrast between these passages, the first from the old version, the second from the new:

The last time I visited the baths I remembered a story a friend had told me one night while we were out cruising for men on a busy street corner. My friend would always get all dressed up, with feathers, gloves, and other accessories.

vs:

The last time I visited the baths I remembered a story that a transvestite on the street told me one night. He liked to dress exotically. He always wore feathers, gloves — that type of embellishment.

Nowhere in the new translation does the narrator call this person his friend. Nowhere in the old translation does the narrator use the word transvestite. But he does say that they are cruising for men together, and both wearing women’s clothes, so it’s not like he’s being euphemistic or coy. The new translation doesn’t implicate the narrator in the friend’s tastes — one could believe that he disapproved of his friend’s attire, where the old version makes it clear that he bemoans the fact that no one in their city appreciates it. This felt deeply, deeply wrong to me.

To properly critique (I mean, APPRECIATE) the new one, though, I would need to read it on its own, and consider what aspects of the text it brings out or illuminates (not just what seems to me to be missing). What tone is produced by the prose — trying to forget the one I know and love.

But I’m not going to do that, because there are other things that I would rather be doing with my time right now (and a lot of other things I need to be doing with my time right now, whether I’d rather or not). I’d rather re-read the old one instead.

2 thoughts on “Beauty Salon, Mario Bellatin”