The site formerly known as twitter has its flaws, but one things I will be forever grateful to it for is that it pushed me to finally undertake the project of reading Cavell’s Pursuits of Happiness and watching all of the movies he writes about. There was a lively thread where people ranked the different movies and chapters, and I could no longer resist the desire to have a strong opinion about the topic.

Do I have a strong opinion on it now? One I’d be able to confidently assert in a tweet? I’m not sure. In any case, reading the book took me months, which I think was the right way to do it — you really need time to process Cavell’s prose. To top it off, partway through I started re-reading the book from the beginning, as the essay I was writing about Sally Rooney’s novels turned into an examination of Conversations with Friends as a comedy of remarriage (look for that sometime next year, hopefully?). Indeed, my experience of Pursuits of Happiness is that you really have to read it several times before it begins to coalesce in your mind — which is maddening, but also thrilling.

Reading it gave me a new understanding of some other thinkers whose work I love — such as Lauren Berlant and Sianne Ngai — who I now recognize as deeply influenced by Cavell (not that either of them hides this, though Lee Wallace does have a fascinating discussion, in Attachment Theory, of how the influence isn’t entirely acknowledged in Berlant’s work. I don’t know if Lauren read it or not (it seems quite likely), but it’s notable that On the Inconvenience of Other People cites Cavell much more explicitly.). It also gave me some insight into the writing style of some other thinkers that I won’t name here (sorry) whose work both fascinates and frustrates me because the way they frame arguments is so opaque, in what I now recognize as a very Cavellian way: associative, meandering, never stating the thesis openly, leaving all kinds of premises implicit.

The Afterword to Pursuits of Happiness is actually a perfect illustration of this: it ostensibly seems to be an argument for studying film in universities, and ends on a grand concluding statement about the university and democracy (I think). Along the way it considers questions of curriculum and the nature of teaching — whether texts (or films) teach you something on their own, just from your own interaction with them, or whether it is the (charismatic) teacher who educates you and the object doesn’t matter (I think he says it’s both); the relationship between film and the “nostalgia for the ordinary” (here there is a very quick contrast between Wittgenstein and Heidegger on the ordinary); Buster Keaton as illustrating a point about Heideggerian Dasein — but also the question of whether Keaton is merely an illustrative example (which is a larger question about the nature of an example and the process of studying philosophy and film); Walter Benjamin vs Robert Warshow; Benjaminian aura and the cultishness of curriculum. How are these different points connected? They’re all related, obviously (?), but they don’t logically follow one from another, except perhaps in Cavell’s chain of thought. And you’ll notice that as I have presented them here, they are a combination of topics, questions, and claims. You’ll further notice that in some places I’m speculating as to the claim or question in parentheticals. Because he doesn’t tell you. He does, sometimes, make an explicit claim, and it’s very exciting, but also orients you far less than you might hope.

This might sound maddening, and ok, yes, it sometimes is, but honestly, by the end, I wouldn’t have it any other way. I absolutely fell in love with his way of thinking and writing. Does it make me feel a little stupid and insecure that I might not have understood, yes, but you set that alongside the moments where there’s this ZAP! of connection and various ideas click, and it seems like a worthy tradeoff. Also, there are these individual sentences that are just perfect little pearls of insight that seem to float miraculously in the air, unconnected to the surrounding lines (what’s that Virginia Woolf line, about ideas as gossamer threads?). I get why other people want to write like this. Though I still suspect that some of them are also just concealing the fact that they haven’t fully figured out their own argument. I am very tedious in wanting people to not only figure out their own point, but also just fucking tell me what it is. Perhaps it is a failing on my part. But for Cavell, I will make an exception.

Anyways, so I loved this, so much that, as mentioned, I immediately found myself writing about it. I want to keep writing about it, and keep rereading it. It’s so lovely, and brilliant, and funny, and charming. There are so many little gems scattered through it that I want to excavate and examine closely.

The book’s overall premise, that there is a specific set of Hollywood talkies that comprises the genre of the comedy of remarriage, is one that I am both utterly convinced by and highly skeptical of. Only these seven films?! Can this be called a genre? Or a microgenre? Is it a firmly closed set? Can’t I claim that it can be transported to other contexts (as indeed I have attempted to claim re: Sally Rooney) and serve more broadly as a conceptual tool? And isn’t Cavell’s interest in this cluster in any case more formal than historical, though it admittedly occasionally dabbles in historical context?

Am I persuaded by the readings of the films? Sometimes. I mean, as mentioned above, I’m not so sure that I always understand the overall argument. But certainly, individual components are stunningly insightful, perhaps most especially when they seem to be stating something totally obvious. The readings were always surprising. This, again, made me feel stupid — shouldn’t I be able to anticipate how he’ll read this one, especially after a few chapters of the argument? — but was also utterly delightful, like you would laugh out loud with the pleasure of it as you read, at these unexpected turns.

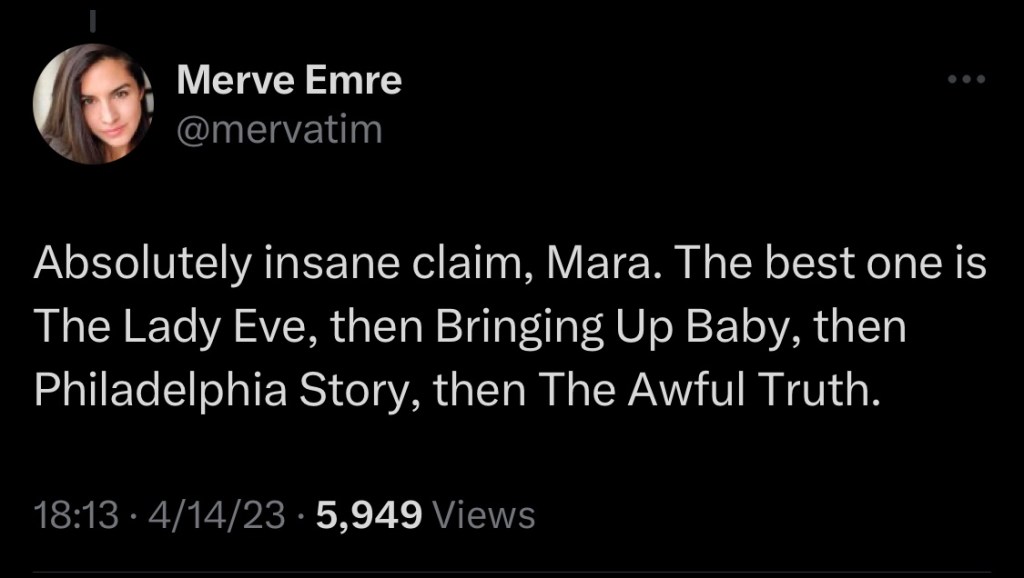

I was worried, when I realized that the chapter many proclaimed as the best, the one on The Lady Eve, was the first. And it’s true, it is the best (how they rank from there is tougher). But that doesn’t mean that it’s all downhill from there. It’s the one that most perfectly unites an innovative (but persuasive) account of the film with the overall concept of remarriage comedy, yes, but then the other chapters explore different facets, illuminating further properties of the genre. And of course, there are the movies themselves — it was my great fortune that I hadn’t seen Adam’s Rib or The Lady Eve before, and I had forgotten that I’d seen the The Awful Truth, and forgotten most of what happened in it, and in His Girl Friday, so there was an added pleasure of watching the movies in a sequence, with the most familiar ones nestled in the middle. I don’t know if I should admit that Philadelphia Story is my favorite of the films; I’m helpless against its charms, but it’s also pretty terrible, ideologically. Maybe this is why it’s the least satisfying chapter of the book, though even typing that, I immediately feel compelled to re-read it, certain that I will discover that I am wrong; I have missed the point; it’s brilliant.

At the end of the book, Cavell returns to this question of whether studying film is worthwhile (this is the part of the book that feels the most dated, the repeated need to justify the pursuit) and asks, “Does one believe that there are films the viewing of which is itself an education?” He has already said there are such books, at the end of a paragraph in which he extols the offerings of the charismatic instructor: “Given teachers with something to love and something to say and a talent for communicating both, you can afford to forget for a moment about curriculum. Whatever such teachers say is an education.” Although these sentences are directly next to the one about books that are an education, I want to say that they are contradictory. Yet this book, perhaps, proves otherwise.